MM Session 14 - The Foundations of Distribution

In the last class, we discussed the foundational concepts of distribution.

Before we began devouring the flesh of the matter, we began by asking, why do organisations exist? Many of you pointed out that organisations exist to solve problems that exist in society. Some of you argued that organisations exist to make a profit, while others argued that they existed to add value. But these are not the reason organisations exist, they are.simply consequences of their existence. The answer to the question is something you can find in the works of Ronald Coase and Oliver E. Williamson . In fact, they got Nobel prizes in 1991 and 2009 for their contributions on the matter.

In simple words, organisations exist to minimise transaction costs, i.e. costs of exchange. Let me illustrate with an example. If you wanted to get some milk to drink, how would you go about getting it? There are a few different ways you can go about it. On the one extreme, you can go to the market place and buy some milk. This is what is referred to as a market place solution. On the other extreme, you could buy a cow and milk it yourself. Which one would you choose? Perhaps, as an individual, it makes sense for you to choose the marketplace solution. But then, let’s say you are a dairy cooperative that wants to make premium cheese to export to Switzerland, you may want to buy some cows and ensure that there is no uncertainty of supply. This is referred to as a hierarchy. In summary, when individuals are faced with a make or buy decisions, and they choose the make decision, organisations spring up. Interestingly, in the example of the cow, you may wonder, why stop with simply buying the cow? Why not grow the grass the cow eats? or the trees that produce the wood to make the sheds in which you keep the cows? At which point do we stop extending the organisation? If this is something you are curious about, you can read more about their theory (transaction cost theory) here.

We can apply the transaction cost theory to contexts featuring distribution as well! For instance, should firms invest in creating their own retailing channels? Or should they involve third party retailers that are found dotted around the retail scape? When we look at the market, we find that different firms choose different approaches. Often, the decision depends on the kind of products they make. Typically, convenience goods are distributed intensely while shopping and speciality goods are distributed with some degree of exclusivity/selectivity. However, this type of simplistic categorisation may not be valid in recent times since the cost of setting up a direct and exclusive channel is very low thanks to the advent of the internet and quick delivery services. Moreover, many firms today make use of what is referred to as ‘multi channel retailing’ or the practice of making use of more than one channel to retail their wares. Given this base, we can try and differentiate what it takes to obtain a selective distribution and how it differs from an intense distribution.

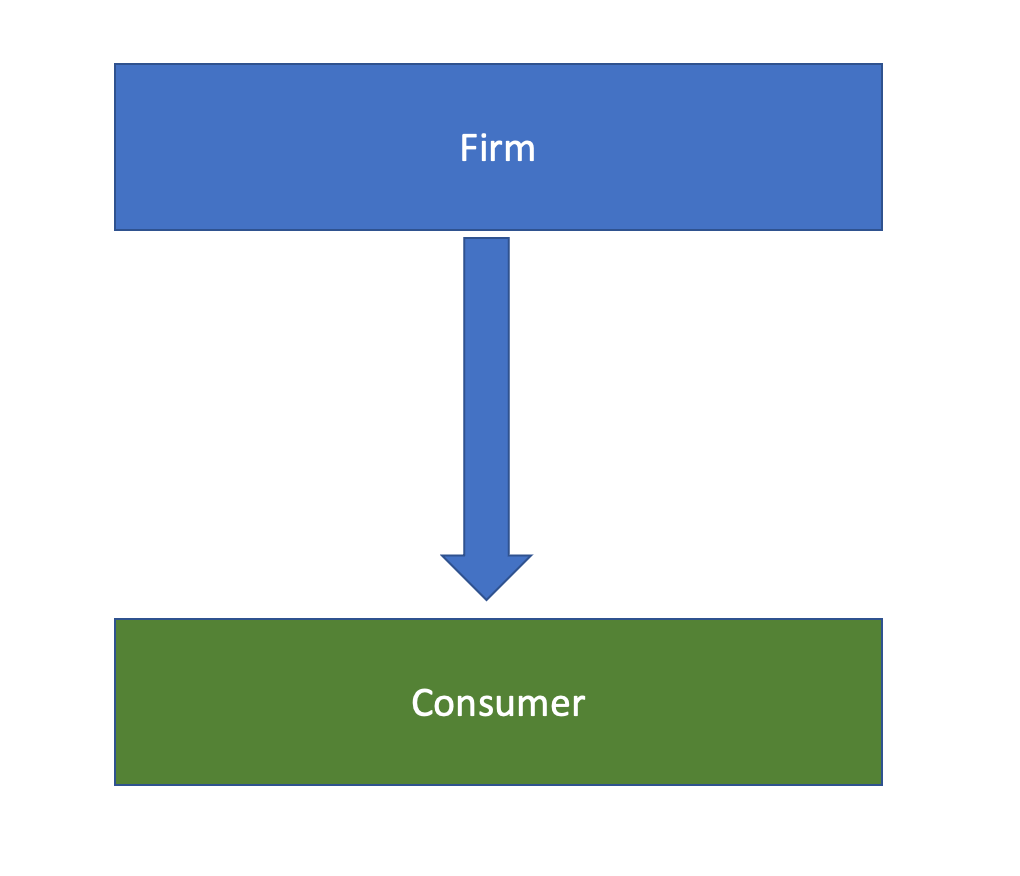

When distributing selectively/exclusively, firms typically want to maintain a direct connect with consumers. This is typically done by setting up firm owned retailing centres. For instance, Apple owns and operates Apple stores around the world to provide its customers with what is increasingly being referred to as the ‘Apple experience’. While this strategy does have its upside, it can prove to be very costly for the firm. Customers too may have to inconvenience themselves to visit the stores. Found below is a diagrammatic representation of a supply chain in a traditional direct selling approach.

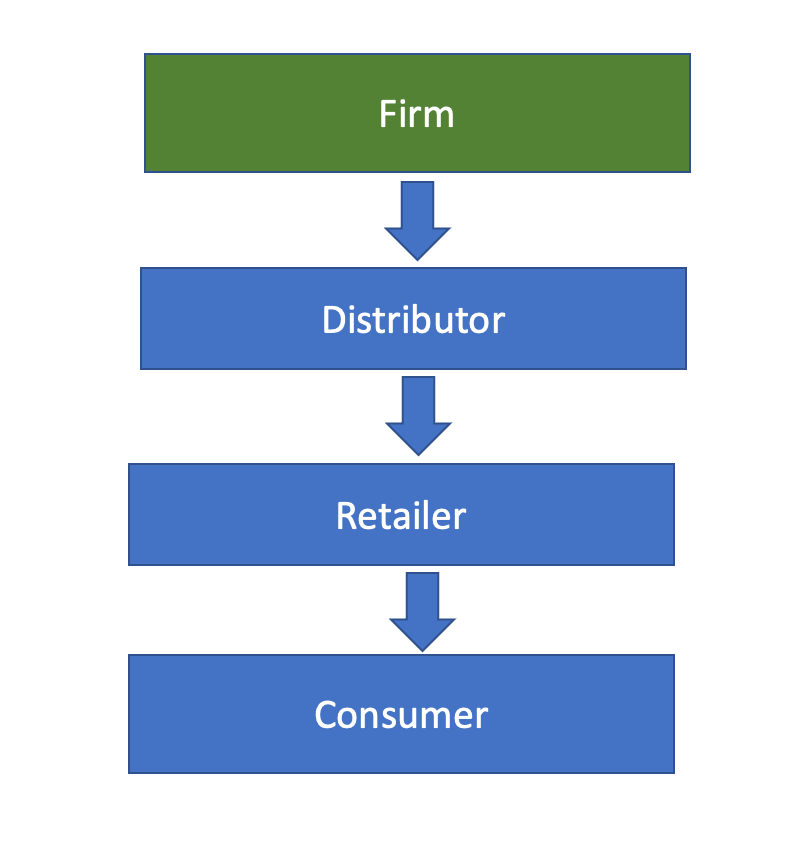

Intense distribution (also known as indirect selling) is somewhat more complicated. Since it involves making products available in easy to access and convenient locations across the market, it typically requires more layers in the supply chain. These layers, are comprised of intermediaries such as distributors, stockists, dealers, sub-dealers, and retailers. It is these characters that make the retail-scape colourful and diverse. Usually, there is a vertical association between them, but there can also be some mixed arrangements from case to case. Found below is a diagrammatic representation of a supply chain in the traditional indirect selling approach. The more the intensity of distribution, the greater is the length of the supply chain (i.e. the more the intermediaries).

There are two important factors to remember here. First, the diagrams presented are purely representational. In reality, a firm can have dozens of distributors and each distributor can service hundreds of retailers. This is not exactly show in the diagram but is understood. Second, as the product moves down the supply chain, money moves up. Typically, each layers of the supply chain adds some value and take a commensurate amount of margin in exchange for it. The value can be added in the form of storage, transportation or even access to credit for downstream intermediaries. If not for the existence of such complex supply chains we may have to travel miles before we get some detergent or soap. Imagine the ridiculousness of such a thought.

Considering that today, companies can easily maintain multiple routes to customers (channels) simultaneously, it may be critical to realise that there can be much interplay between coexisting channels. This makes way for a political economy of sorts. In many ways, it is the handling of this political economy that is at the heart of the job of a sales manager.

In the next class, we will put ourselves in the shoes/tyres of Castrol’s sales managers and try and solve the ‘Castrol India Limited an Innovative Distribution Channel’ case written by Dr. Renuka Kamath, who is now an Associate Dean at SPJIMR, Mumbai.

Happy learning!

Look forward to an exciting class discussion!