Middlemen in Indian Agriculture

Introduction:

Over the past 70 years, India has had tremendous successes and massive failures in the field of Agriculture. On the bright side, there was sustained agricultural growth since Independence that helped the nation transition from a situation of dependency during the late 40s, to green revolution led nascent self-sufficiency during the 70s and 80s, and into commercialization and globalization after liberalization in the 90s (Pingali & Shah, 2001), while on the other end of the spectrum, as many as 2000 farmers a day, many of whom were young and educated, commit suicide due to crop failure, decreasing social status and perhaps most importantly, the inability to pay back loans taken to buy increasingly expensive farm inputs (Sainath, 2013) . The government actively highlights its achievements while it actively underplays the rampant increase in rural poverty, dominance of informal money lenders in agriculture, stagnation of technology, the harmful effects of the lack of constant irrigation and changing climatic conditions, farmer suicides and the lack of follow up on welfare schemes launched to benefit the farming community (Gruére & Sengupta, 2011; Mohanakumar & Sharma, 2006; Kaushal, 2015). Although there exists no consensus among the government and various other stakeholders in as far the current state of the Indian farmer is concerned, one point of agreement among all parties is the need to reduce the role of the agricultural middlemen. In this term paper, I aim to understand the origins and the changing roles of the ‘modern middleman’ and propose some policy suggestions that may help reduce dependence on them.

Origins:

The Oxford English Dictionary defines the middleman as ‘a person who buys goods from producers and sells them to retailers or consumers’. Although true in the strictest sense of the word, this definition fails to account for the plethora of intermediary roles such as a transporting, storing, financing, processing and sorting that middlemen perform. Historically, the rise of the middlemen and the rise of the cities were parallel processes that reinforced each other. As cities swelled up with people, it became necessary to funnel large quantities of food from the ‘rural’ countryside to the ‘urban’ centres. A class of middlemen began to emerge to bridge the supply and demand for food. It was only by the start of the twentieth century when megacities with millions of inhabitants began to appear across the globe that a more sophisticated network of middlemen to consistently provide cities with fruit, vegetable and grain became necessary. In possibly the first effort of its kind, W. P. Hedden, in his book ‘How great cities are fed’, paints a vivid account of how the middlemen in the United States, particularly those handling the transportation of food from the food producing rural regions to the urban centers in New York, held the city hostage. A lot has changed since then. Growing consumer demand for a more extensive variety of food has added multiple additional layers of complexity to the commerce of the agricultural value chain. To address this demand, intermediary middlemen began performing various vale adding functions such as aggregation, storage, processing, transport and retailing. In exchange for these activities, they also seek a constant and possibly increasingly significant share of the value derived from the value chain. Unlike the farmers who work several months to produce, these intermediaries do not face any risks in the production of grains but retain a guaranteed profit potential. They utilise their position within a complex political economy to merely buy low and sell high, generation after generation. In essence, the middlemen benefit from both the sweat of the farmer and the toil of the average consumer.

Over the course of the past seventy years since Indian independence, middlemen have also acquired both economic and political power to secure their positions in the rent-seeking comfort zones they have installed themselves in. In addition to the various other reasons that we know of that causes farmers to lose interest in their profession and move to the cities, the increasing power of the middlemen in the value chain needs to be highlighted. It may be argued that it is because of these middlemen that prices get inflated considerably, and farmers hardly get fair compensation for their produce. Consequentially, India faces a looming agrarian crisis with protests erupting across the nation on an almost daily basis.

History of Middlemen in the Indian Context:

In India’s colonial past, the British introduced the Zamindari system as a means to levy taxes. The zamindars and his subordinates collected land taxes, in either cash or kind, from the peasants who tilled the land. Ten elevenths of the taxed revenue were then passed over to their British overlords. It was through a network of zamindars mostly in the North, Ryots and Mahalwaris in the south that the colonists were able to ‘farm’ taxes from India much to the detriment of the tillers themselves. It was these zamindars, whom Tagore famously called, “the parasites of society”, who syphoned off large portions of the wealth created and ensured that cultivators were left with little to survive on. They were able to accomplish this using a multi-tired system of middlemen who each took their ‘fair share’ of compensation in exchange for the services rendered[1]. By ceaselessly exploiting the agricultural workers through subinfeudation and increasing indebtedness among the farmers, these middlemen wreaked havoc on the Indian economy. It is important to note that these individuals typically came from the middle classes, and were also involved in tasks such as trading and money lending that enabled them to secure other sources of income. The money lenders of Bengal for example, controlled the Bengali agrarian system and individuals who took loans from them on ‘Dunobari’ or ‘Derabari’ from them often lost their land due to inability to pay back the principal with interest[2]. They often resorted to coercing the farmers, who were both economically and socially weaker, through a combination of physical threats, verbal abuses and social pressures. The zamindari system was identified to be one of the critical reasons for the distress that farmers faced. When India got independence in 1947, the zamindars and the many layers of middlemen who worked under them were abolished, and the land was redistributed to the tillers of the soil. The middlemen were for the time being, weakened, only to reappear a more virulent force in the near future.

The modern middlemen began to appear in the Indian agricultural landscape with the emergence of the agriculture produce marketing corporations (APMCs). The AMPCs which were set up as a result of the enactment of the APMC Acts in the 1960s were, in principle, a step in the right direction towards enabling the farmers to sell directly to the consumers. However, since it was possible for farmers to be exploited by large sellers, the State prohibited farmers from engaging any form of direct dealing with them. Instead, the farmers would have to sell their produce directly to licensed ‘market functionaries’ or middlemen as they are more commonly referred to. These middlemen acted as commission agents who purchased the goods from the rural farmers and sold the produce to consumers at the APMCs. Since it was not feasible for the farmers to individually own equipment to transport their produce, middlemen began to offer transportation as a service in exchange for a fee. Similarly, businesses such as selling fertilisers, seeds and other farm equipment were all comprised of a new breed of middlemen who were shielded from the climatic risks and the market risks that the farmer faced and had a guaranteed source of income throughout. Additionally, they faced little price competition as they had cartelized the supply of many essential services to the farmer by means of caste, community and family. In essence, their function was to offer a service for a fee, being completely freed from any of the risks that agriculture posed.

Due to the lack of competition among middlemen, the quality of the services they offered had not risen. The cartelization ensured that the price also was consistently increased disproportionately to the value they added. Due to these reasons today, it is the middlemen who are blamed in large part for the abnormally large differences between wholesale and retail prices of most commodities. Although this has hurt both the electoral prospects of politicians and the pockets of the larger Indian population, there seems to be no change in the situation on the ground.

Why Modern Middlemen are Necessary?

Nothing exists without reason. The modern middlemen too were created with sound logic in mind. To understand the reason for their existence, we must begin by understanding the growth of the Indian agriculture scenario in recent times.

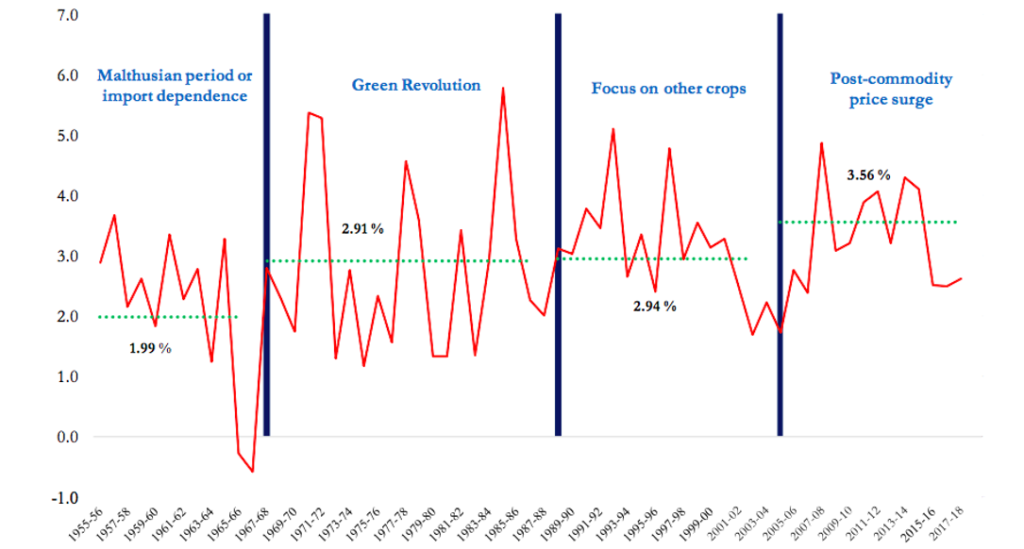

The story of Indian agriculture after independence may be split into three parts- the Malthusian period or import dependence era between 1955-68, the green revolution era between 1968-90 and the Liberalization era from 1991 onward. The real agricultural growth rates during the three eras are shown in the graph below.

Figure 1: Real Agricultural GVA Growth in India, 1960-2016- Sourced from The Indian economic survey 2017-18

It is important to note that there has been an accelerating growth rate over the course of the last 60-70 years. This growth was in large part due to the agricultural development planning post-independence. The then Congress government had chalked out a plan to ensure that India improved its food grain production (especially the spices due to their value as a protective food), to reduce regional imbalances in agriculture performance, encouraging agro-raw material production, securing fair prices for the farmers and improve irrigation to farmlands across the nation. Many of the above-mentioned objectives had not seen any major changes during the early years of independence. It was only at the start of the green revolution in 1967-68 when technological innovations began to be introduced into agriculture that significant changes began to be felt.

Changes such as the usage of genetically modified crops as opposed to traditional seeds translated into greater risks for the farmer as most GM crops were designed to be used in irrigated continuously farms. In India however, large tracks of land were (and are) largely raid fed. The seeds that were reaped out of genetically modified plants were sterile and hence could not be sowed subsequently. This meant that the farmer had to procure the seeds he needed every time from the seed merchant. It was around the same time when the State pushed towards the marketization of agriculture as a whole. Various parts of the agricultural value chain were being transformed from the traditional setups to modernized market led systems. This was necessary because a well-knit network of market intermediaries was required to take GM seeds and NPK fertilizers that would catalyze the green revolution to the farthest reaches of India’s rural heartlands. The current structure of agricultural value chain in India was what was aimed at by the state as it licensed various middlemen, who had economic, political and social capital to enter into the value chain and burrow a position for themselves in the long run.

Bourdieu’s Forms and Capital and Roulette wheel:

The French philosopher, Pierre Bourdieu viewed capital, in its multiple forms as, accumulated labour (Bourdieu, 1986). He discusses economic capital, social capital, symbolic capital and cultural capital. By comparing the process of capital accumulation to a roulette wheel, he states, “Roulette, which holds out the opportunity of winning a lot of money in a short space of time, and therefore of changing one’s social status quasi-instantaneously, and in which the winning of the previous spin of the wheel can be staked and lost at every new spin, gives a fairly accurate image of this imaginary universe of perfect competition or perfect equality of opportunity, a world without inertia, without accumulation, without heredity or acquired properties, in which every moment is perfectly independent of the previous one, every soldier has a marshal’s baton in his knapsack, and every prize can be attained, instantaneously, by everyone, so that at each moment anyone can become anything”. Implying that those who possess capital, in any form, would be able to create more with relative ease when compared to those who did not possess any form of capital.

This logic can be applied to understand the power struggle within the Indian agricultural value chain. The middlemen, who possess different forms of capital- such as economic capital (money), social capital and cultural (caste) were able to successfully produce more value for themselves through complicated political, economic activities. The farmers, on the other hand, stripped of all forms of capital, were left with the bare necessities that allow them to survive merely.

The Indian Farmer, Marketization and Modern Commerce:

The average Indian farmer, who traditionally produced for his consumption and sold or bartered the surplus to provide for himself became increasingly dependent on market institutions to source inputs and sold his produce. This is most evident when we take a closer look at the fertilizer consumption of the Indian farmer. Fertilizers (which are produced predominantly by the private sector) consumption in India has increased from 0.069 million ton in 1950-51 at a CAGR of 12% to 16.2 Million ton in 1997-8, a 234-fold increase[3]. During the same time frame, food production increased from about 51 million ton to 192.2 million ton, a mere 3.77-fold increase. Similarly, in the case of sourcing credit, another key input of production for the farmer, transformed from being characterized by informal agents such as moneylenders who charge higher interest rates to compared institutional sources, which by some estimates account for 60% of all credit dispersed[4]. This data points to the increasing marketization of the Indian agriculture landscape.

With increasing marketization and modernization, state sanctioned middlemen started using their capital and business acumen to establish a strong position for themselves in the political economy of agriculture. The State which aimed to reduce the exploitation of farmers ended up creating an entirely new class of exploitative middlemen. Many middlemen exploited the farmers by building either providing farmers with critical resources, political maneuvering or caste based social pressures. In many states, the schemes that were meant to relieve the farmers of their distress were used up by middlemen. Their shielded position from the worries of production and free access to markets enabled the middlemen to experience consistent growth spanning several decades as the poor farmers watched inequality build up right under their noses.

With time, a system of several layers of middlemen were created, this increased both the length of the value chain and the possibility of cartelization (Nayak, 2018). The combination of power and money in the hands of a few ‘middle’-men effectively ensured that the farmer’s selling price was pushed down, while at the same time pushing up the price to the consumer.

Today, we have a situation where there is a widening gap between the retail prices and whole sale prices. In some retail outlets, the differences are found to be as high as 150% (Kasabe, 2018). While the government actively tries to bring down the whole sale prices, it needs to be remembered that not the whole of the wholesale price is captured by the farmers. The commission agents in the APMCs take away a significant chunk of the value from these well-intended market transactions. Additionally, it is middlemen who also contribute to farmer inputs such as seeds and fertilizers that also contribute to an increasingly significant cost to the farmer. For instance, between 2011 and 2015, the average price of fertilizer doubled and continued to be on an upward trend (Himanshu, 2018).

The markets were regulated by key actors who typically belonged to certain ethnic identities (Pain & Pain, 2007). The social capital that they possessed allowed the middlemen to dictate terms which may be considered irrational from the view point of the market. For example, Kapadia (2009) shows how middlemen were able to dictate less than fair wages through ‘negotiations’ with female Muslim beedi makers. Heyer (2007) in her study of villages in South India, contends that the institution of caste has been used to brutally subjugate and the lower classes specifically and the working classes in general. It is in the urban centres of the country where there is a large population with growing purchasing power that the middlemen seek their profits. By the time a fraction of the produce is sold at predefined prices, the middlemen recover the investments and some profits. However, they continue to charge premium prices for the remainder of the goods which in turn leads to large quantities of consumable food rotting and being thrown away.

Arguments Against Middlemen:

The high degree of involvement of middlemen in trade channels is often explained by a functional argument. That is, the middleman’s role is to provide value to both the sellers and the buyers. This role of the middlemen during preindustrial times was necessitated due to the lack of transportation and communication infrastructure and wide disbursement of the industry. This led the middlemen to thrive in the agricultural supply chain (Van Driel, 2003). However, in the modern epoch, their role is becoming increasingly obsolete. This is proven by the fact that the Food Corporation of India allowed 46,658 tonnes of food grain to rot, food grains that could have fed millions of people (Chethan Kumar, 2018). The middlemen, had they been efficient economic entities, could have sold the food at or below market price to capture economic value failed to do so. Food was therefore simply wasted, adding little value to both the producer and the consumers and causing food inflation. The role played by middlemen in causing food inflation is underplayed by politicians and rarely highlighted by the press. Rampant corruption ensures that their access to financial capital allows them to indulge in is part of the reason. The middlemen and members of the communities constituting middlemen often finance political parties to ensure that the politicians look the other way. Their importance on the political stage can be exemplified by the fact that Mayawati, the former chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, India’s largest state, used to call for ‘Baniya Sammelans’ to appease the members of the Baniyas, a powerful middlemen community who are actively involved in trading, wholesaling and moneylending. In the south, the Chettiyar community that is involved in trading, jewelry mortgage and gold jewelry making has a similar position in the value chain. Further investigations in the working of such middlemen communities among many others distributed across the country are required before structural changes can be planned.

Emphasis has to be laid on the fact that he middlemen have also contributed positively to the agro-value chain. It is the middlemen who invested capital in value-adding services such as cold storage, transportation infrastructure, preserving and processing of food items, however, it needs to be highlighted that there is much left to be desired in these areas in as far as India is concerned (Sharma, 2018).

The Resurgence of Money Lenders:

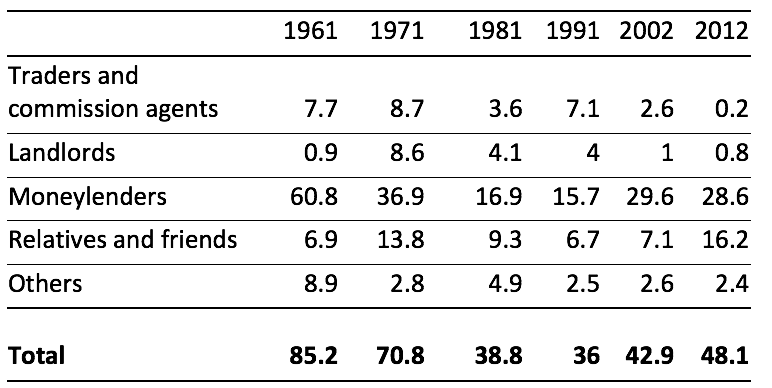

Another worrying trend that is noteworthy is the resurgence of moneylenders as a means of finance for the farmers. Due to the planned actions of the State during the 60s and 70s caused the moneylenders’ power in the equation fall drastically. However, in the past 20 years there is market resurgence of informal moneylenders as a source of debt for farmers. Table 1 shows the data cited from Ghosh & Kumar (2015).

One argument to this data trend may potentially arise from Polzin (2015) who discusses the fact that the increase in transportation infrastructure and the falling real transport costs to have increased the level of informal lending in Arni, Tamilnadu. Should that be the case, the increasing trend should have continued into 2012 as transportation became increasingly accessible to the general public. Also, the NSSO data points to an increase in the sheer number of money lenders since the early 1990s. It needs to be highlighted here that the interest rates that the money lenders seek as opposed to what the formal establishments seek are exorbitant (RBI, 2014). This rising trend, especially in the face of a rapid increase in microfinance institutions across the country is worrisome.

The recent demonetization of large denomination currencies was said to have aimed at removing black money from the economy. Since it was the middlemen who hoarded black money for ages, it would also be interesting to find out what effect the demonetization had on the interest rates at which farmers were lent money informally.

Conclusion:

After the liberalization of the Indian economy, the state has neglected making investments in rural infrastructure. This is one of the chief causes of the deceleration/stagnation in agricultural growth in recent times. Should this trend continue into the future, it would result in the creation of two societies within the nation. The interest of small farmers needs to be kept in mind to ensure that the divide does not widen further and is narrowed in the not so distant future. The increasing marketization of farming-related activities has pushed the cultivators from facing not only climatic and societal risks but also market-related risks. Smallholders have a little marketable surplus and face higher marketing and transaction costs in selling it in distant urban markets (Birthal et al. 2005). Farmers who faced social shackles in the form of caste-based discrimination now have to handle the double burden of social marginalization and market-based risks. The distressed farmer is forced to buy seeds from the market when the demand and hence price of seeds are high during the sowing season, on the other hand, the very same farmer sells his produce when there is a huge supply that results in significant lowering of prices. In effect, the farmer pays a substantial risk premium to participate in the markets. The lack of economic capital effectively increases the costs of market participation to the farmers. Additional burdens are posed by the middlemen who have over time gained expertise in their respective occupations and can extract a larger premium from the retail prices charged to the consumer. They have done this by effectively high jacking the farmer-friendly initiatives and deriving value from them at the expense of the farmer. In effect, the farmer is boxed into a precarious situation from which he may never escape but for a targeted effort from the State. Recent times show promise as states have begun changing their respective APMC laws to allow farmers to directly sell to retailers through contract farming. However, it is important to look for solutions to the looming crisis at hand.

One possible solution to the current conundrum in the agriculture value chain could be to add banks as an additional layer of middlemen who could buy directly from the farmers and sell to the middlemen for a slightly higher fee. In exchange, the banks could also provide the farmers with crop insurance to cover the market risks that the farmers face. Over time, the commission agents and the other layer of middlemen could be systematically removed from the equation thus freeing up value for the farmer and the consumer to enjoy.

References:

Bourdieu, P. (1986). Pierre Bourdieu 1986 – The forms of capital. Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, 241–258. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470755679.ch15

Chethan Kumar. (2018). Grains rotting with FCI could have fed 8L for a year, 8–9.

Ghosh, S., & Kumar, R. (2015). Monetary policy and informal finance: Is there a pecking order?, (65243).

Gruére, G., & Sengupta, D. (2011). Bt cotton and farmer suicides in India: An evidence-based assessment. Journal of Development Studies, 47(2), 316–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2010.492863

Heyer, J. (2007). The marginalisation of Dalits in a modernising economy.

Himanshu. (2018). India ’s flawed fertilizer policy, pp. 1–5.

Kapadia, K. (2009). Liberalisation and transformations in India ’ s informal economy Female breadwinners in working-class households in Chennai, (Fakhri 1999).

Kasabe, N. (2018). Survey finds huge gap between wholesale , retail pulse prices, 1–7.

Kaushal, A. (2015). Confronting Farmer Suicides in India. Alternatives, 40(1), 46–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0304375415581258

Mohanakumar, S., & Sharma, R. K. (2006). Analysis of Farmer Suicides in Kerala. Economic and Political Weekly, 41(16), 1553–1558. https://doi.org/10.2307/4418114

Nayak, D. (2018). Farmers Struggle to Escape Middlemen, 2–4.

Pain, A., & Pain, A. (2007). The Opium “ Revolution ”: Continuity or change in rural Afghanistan?

Pingali, P. L., & Shah, M. (2001). Policy Re-Directions for Sustainable Resource Use. Journal of Crop Production, 3(2), 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1300/J144v03n02_05

Polzin, C. (2015). Institutional Change in Informal Credit: Through the Urban–Rural Lens. Middle India and Urban-Rural Development: Four Decades of Change, 1–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-81-322-2431-0

RBI. (2014). Report of the Expert Committee to Revise and Strengthen the Monetary Policy Framework.

Sainath, P. (2013). India Losing 2,000 Farmers Every Single Day: A Tale Of A Rapidly Changing Society. IB Times. Retrieved from http://www.ibtimes.com/india-losing-2000-farmers-every-single-day-tale-rapidly-changing-society-1232913

Sharma, N. C. (2018). India ’ s greatest need is for an effective cold chain solution that can integrate the supply chains for agricultural commodities from production to consumption centers , experts say. Livemint, pp. 2–5.

Van Driel, H. (2003). The role of middlemen in the international coffee trade since 1870: The Dutch case. Business History, 45(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/713999313

[1] Ashok Majumdar, The tebhaga movement, pg 37

[2] Ashok Majumdar, The tebhaga movement, pg 38

[3] (Sharma and Sharma, 2000) c.f. The State of the Indian farmer, Book 8, Input management, pg.59

[4] C.H.Hunumantha Rao, The State of the Indian farmer, pg.35