CB Session 6 - Preferences and Choices

The case of Zerodha

Introduction:

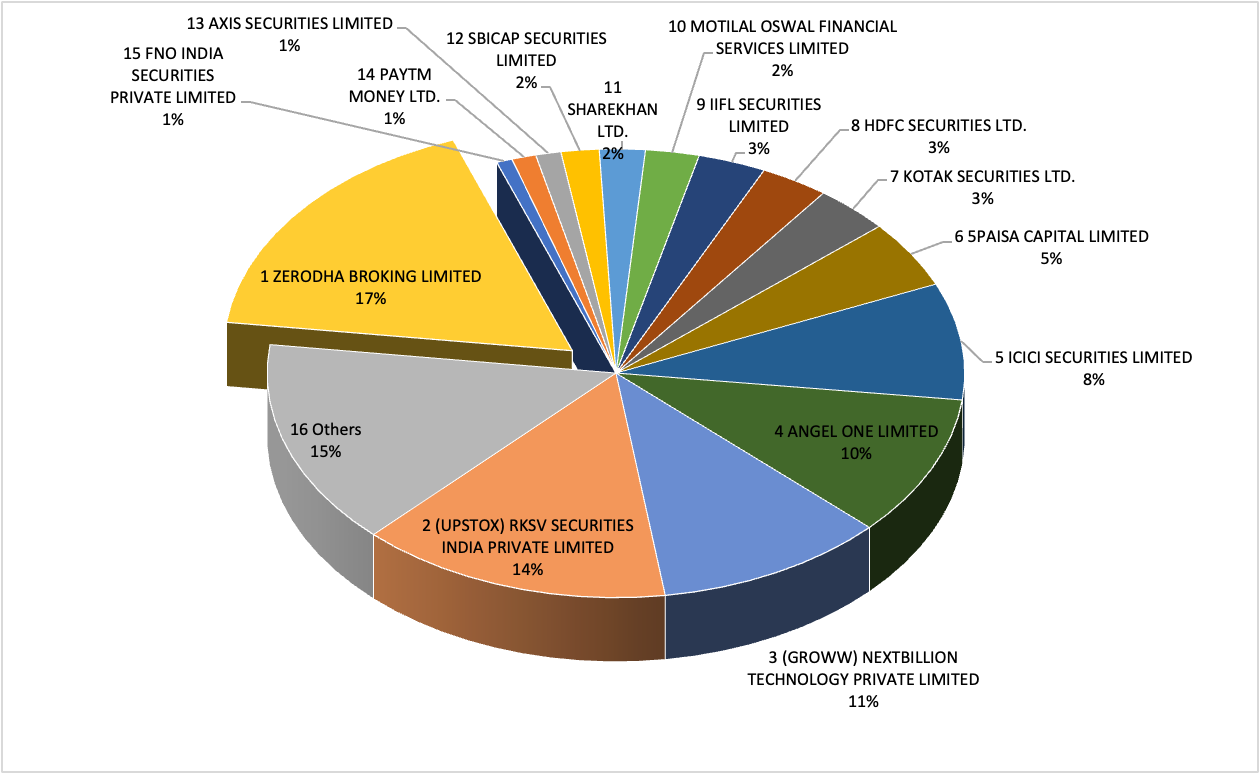

In today’s class, we discussed the case of Zerodha - the discount stock broking firm. According to NSE data from March 2022, Zerodha held 17% of all unique clients in India and reigned as the market leader (See Exhibit A for more details). An impressive feat for a company that has existed for just under 12 years at the time of writing. The question that one needs to ask here is, “how did Zerodha achieve this significant achievement?”.

Thanks for reading Karthikeyan’s Newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Subscribed

Today’s class discussed “Zerodha: Sustaining A leadership position in India” by Dr Vipul Kumar Singh and Dr Sandeep Puri. Since the case was published just before the recent Covid-19 pandemic (the date of publishing was 20.09.2019), it does not cover a lot of details about how COVID 19 helped catapult Zerodha and other online-only stock brokers even further uphill. However, the case does paint a nice picture of the origins of Zerodha and the business model it follows. Since the last few years were packed with a lot of action in this industry, I am appending some more resources to bring you to speed.

Additional Resources:

Before we begin dissecting the case from a consumer behaviour perspective, I would like you to have a look at the following resources that are available online for free:

- https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/markets/expert-view/we-have-been-adding-over-200000-new-customers-every-month-zerodha/articleshow/77929518.cms?from=mdr

- https://zerodha.com/ - to understand the products and services that they have on offer

- https://www.topsharebrokers.com/compare/icicidirect-vs-zerodha-vs-upstox/1/18/33/

- https://www.business-standard.com/article/markets/millions-of-millennials-are-piling-into-india-s-stock-market-shows-data-121032500065_1.html

Please also check out the following videos:

Principal agent problem:

Also, please look at this: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Principal–agent_problem, for an overview of what is better known as principal-agent problems in economics and business studies.

Simply put, when a principal (like you and me) delegates a task (like buying shares from the market) to an agent (like a stock broker), the agent may not always act in the best interest of the principal. It is fully possible that the agent decides to act in a manner that benefits him/her and not the principal. For instance, a stock broker may want to maximise his revenues by making you indulge in more trade volume, while you may be interested in increasing your overall profits and not volume of trade. This difference in objectives between the principal and agent is a the fulcrum of all principal agent problems.

(Note: there are two major types if principal agent problems. The one we discussed just now is called the moral hazard problem. There is another problem called adverse selection that you may benefit from looking at).

The CB perspective:

At a fundamental level, consumers make product purchases when they have a problem. It may be rational to expect that consumers may not try to make changes if they are happy with the status quo.

Typically, consumer problems may be recognised in one of two ways - when the ideal state is significantly better than the consumer’s actual state (imagine going around in a bullock cart while everyone is zooming past in SUVs) or when the actual state falls well below the ideal state (imagine getting a pay cut and not being able to afford the things you used to).

After recognising the problem, consumers go around searching for information, and evaluating the alternatives that they think best suit them. At this stage, they consider various options on the basis of various ‘evaluation criteria’, heuristics or rules of thumb, and signals that they receive from the brand or manufacturer. Past experiences and opinions of other influencers may also play a key role in determining the decision. It is at this point that they make a choice.

In the context of our case, the problem arises because of the principal-agent problem that may arise between consumers and stock brokers. Historically, stock brokers have been somewhat opaque with financial matters. Very often, they do not communicate all the fees that they are charging to consumers beforehand. Some of these issues carry on to this date. It is in this context that Zerodha helps enlighten customers about a superior ‘ideal state’, one in which they do not have to pay a % commission, but a flat fee. Additionally, Zerodha also promises to be very transparent with all its dealings to consumers. Rightly, what Zerodha has to offer, creates an elevated ideal state that consumers may be willing to explore, especially if their ideal state entails plenty of hidden charges, variable fees, and practices consumers think are unfair (would you feel charging a % fee for a transaction that costs the same despite its size is fair?).

Zerodha also been able to use technology to attract the younger generation of investors in India. Accordion to various newspaper reports (such as https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/markets/stocks/news/burned-out-broker-got-rich-aiding-millennials-trade-for-free/articleshow/69248060.cms?from=mdr), Zerodha better understood the change in consumer behavior and positioned itself uniquely to take advantage of this change. What the case does not fully cover is the fact that in many ways, Zerodha had built an ecosystem consisting varsity, coin, small case, and ditto that offered a comprehensive set of solutions for all financial needs of young Indian investors who Zerodha was targeting. The use of a mix of technology and education helped Zerodha capture markets that were fast growing due to various macro economic factors such as demonetisation, digitisation, increased mobile connectivity, and more recently, work from home.

In many ways, the case discusses how a firm was able to observe a trend amongst consumers and make use of the resources it possessed to capture value from the trend. Given that many of Zerodha’s current customer’s a still very young, and unlikely to be earning sizeable salaries, one may expect that its founders, the Kamath brothers, are sitting on a gold mine that is yet to fully materialise. Here are a few questions that I think you should ponder over:

Questions to ponder over:

- To what extent can transparency help? Is there such a thing as over transparency? Is transparency easy/cheap to be provided?

- If you were going to start a brokerage firm today, how would you go about it?

- During Zerodha’s rise to market leadership, what did other consumers end up doing?

- Do you think Zerodha’s customers will continue to stay with the service in the years to come?

The way forward:

Try and understand how the learnings from today’s class can be generalised into other settings. Are the stages of consumer decision making likely to be different for different products and services? Do all consumers start from scratch when they try to make a consumption decisions? Is there some sort of ‘feedback loop’ that exists that educates consumers over time? Think along these lines. We can take them up during our next class when we discuss in greater detail the consumer decision making process. There are no cases for next class, but then, do read up. Here are some free resources that you may want to look at: